When I was thinking about the title of today's article, I thought of my favorite book in 2023, "What I Learned About Investing from Darwin." I would like to express my gratitude to Mr. Pulak Prasad, author of "What I Learned About Investing from Darwin", for sharing his wisdom and learnings during his journey. Therefore, I picked today's title: "What I Learned About Investing from Carpenters."

What I Learned About Investing from Darwin

I have always wanted to write a reading reflection on "What I Learned About Investing from Darwin". To summarize in one sentence - "What I Learned About Investing from Darwin" is my favorite book this year. My general reading habit is to first read the summary and table of contents of the entire book, then choose interesting chapters to read the chapter…

Now, before you get any ideas, I'm not referring to The Carpenters, the band—although 'Yesterday Once More' remains a high-ranking favorite in my playlist—but rather to actual artisans who work with wood.

The spirit of craftsmanship has always been a topic that fascinates me. Today, I want to share my learnings and reading notes on 木のいのち木のこころ―天・地・人 (The Life of Trees, the Heart of Wood), one of my favorite books from last year.

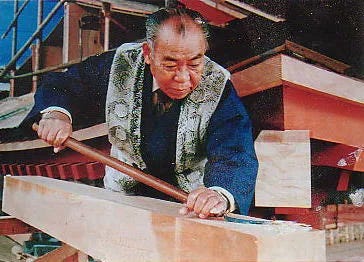

This book is based on a decade-long series of interviews by author Shiono Mitsuaki with Japanese palace carpenter Nishioka Tsunekazu and his three generations of apprentices. It not only showcases the philosophical approach and respect for natural laws of Japanese palace carpenters but also tells the story of Nishioka Tsunekazu, known as a master carpenter in Japan, and his apprentices, highlighting how they preserve and pass down ancient craftsmanship that has lasted for hundreds of years.

I will explore the four themes from the book that interest me the most in the first four sections. Subsequently, as a learner and investor, I will reflect on what I learned from the core spirit, wood philosophy, and architectural wisdom of these palace carpenters.

Given that this book does not currently have an English translation (available in Japanese here), I will provide more additional context and examples to enrich the reading experience.

Enjoy reading!

To begin with, I would like to introduce the main character and the historical context of the book.

Nishioka Tsunekazu was born in Nara Prefecture, Ikaruga Town, Horyu-ji Temple, and followed in the footsteps of his grandfather, Nishioka Tsuneyoshi, and father, Nishioka Narakazu, as a master carpenter for Horyu-ji Temple.

At the age of sixteen, he formally began his apprenticeship under his grandfather. By twenty-seven, he was recognized for his expertise in soil analysis during the dismantling of Horyu-ji Temple and was appointed as the master carpenter. In 1959, he constructed the five-story pagoda of Myokoin Temple, and in 1967, he began building the three-story pagoda of Horin-ji Temple. In 1970, as the master carpenter, he started the reconstruction of the Daibutsuden and the west pagoda of Yakushi-ji Temple, reviving the lost tools of Tang Dynasty palace carpenters, such as the "gunba." In 1977, he was recognized as a holder of cultural property preservation techniques and received the Cultural Merit Award in 1993.

He was known as the "last palace carpenter" who passed down temple construction skills from the Asuka period to future generations.

Nishioka Tsunekazu passed away in 1995.

The Core Spirit of Traditional Craftsmanship - Slow is Fast

I. The path of apprenticeship for traditional carpenters has no shortcuts. It can only be achieved through gradual refinement.

Although everyone learns at a different pace, with some grasping concepts quickly and others needing more time, this doesn't mean that being slow is bad. On the contrary, those who are trained through slow and deliberate practice often become more solid in their skills. The seemingly redundant time and processes are actually crucial because they allow knowledge and skills to deeply penetrate the body, making them unforgettable once learned. These processes, though appearing unnecessary, are important and essential.

In the world of carpentry, some people aren't bad at remembering, but their minds can't fully accept or understand certain concepts. However, through repeated operations, they gradually come to understand and master them. In the long run, these individuals are more likely to become renowned craftsmen compared to those who claim to understand everything at once. The body and hands, after long-term practice, begin to move on their own. The hands naturally move in sync with the brain, making work incredibly enjoyable. As carpenters who work with wood daily, we gradually understand wood, including its quirks and characteristics—things that cannot be taught through language or text. Our motto includes phrases like "The wooden construction of temples and pagodas does not adhere to strict measurements; instead, it is tailored to the unique nature of the tree iteself," which you can't fully grasp unless you truly understand the nature of wood.

As someone who makes a living from craftsmanship, I deeply feel that a craftsman's work cannot be replaced by machines. Becoming a good craftsman requires a long process of cultivation, with no shortcuts or quick paths—only a step-by-step journey forward. This differs from school learning, which isn't just about memorizing with your brain, but requires you to slowly experience and accumulate knowledge, inheriting the techniques and wisdom passed down by your ancestors. Every task starts from the basics; you can't move to the next step without fully understanding each one. Therefore, no matter what you do, you'll encounter basic problems that you must solve yourself.

II. Craftsmanship isn't just about how skilled your hands are; it comes from your personal inspiration and intuitive judgment of things, which are developed through countless experiences.

The Philosophy of Wood and a Perspective on Nature

I. Understanding Wood

In the world of palace carpenters, wood is an indispensable material. Building palaces and temples cannot be done without it. Technically speaking, if you don't understand the nature of trees, you cannot use them effectively. Therefore, I always emphasize that "palace carpenters must first learn how to treat trees," which is basic knowledge that craftsmen must master.

However, today, there are very few craftsmen who truly understand this. The ancient sayings passed down by craftsmen, such as "building temples doesn't involve buying wood but buying mountains; the wood needed must be personally selected from the mountains" and "using wood according to its growth direction" and "building temple structures not according to measurements but according to the tree's nature itself," have gradually been forgotten.

II. A Perspective on Nature

My words might sound exaggerated, but craftsmen indeed need their own worldview. When facing nature, which is infinitely greater than us, we need to reflect rather than calculate prices as soon as we see a tree. Even with an ordinary tree, we need to consider the environment in which it grew, how it competed with its peers, and how wind and sunlight affected its growth. We must respect its growth environment and the character it has developed, and use it effectively. Otherwise, even the most valuable trees will be wasted and not last long in construction.

Nowadays, this work is largely done by wood companies, where you only need to tell them the required dimensions of the wood. Using wood appropriately based on its material is becoming less common. If your eyes can distinguish the properties of wood, you can judge what kind of wood it is. However, craftsmen with such discerning eyes are becoming fewer. This change is because people are pursuing more convenient and faster methods. While completing work quickly is not bad, if you only seek speed without considering the specific situation, it will lead to drawbacks.

III. Approaching Nature Without Shortcuts or Rush

In the past, my grandfather's generation would plant new tree saplings when building new temples. Their idea was that two hundred years later, when the saplings grew into timber, they could be used to repair ancient temples or build new houses by future generations. People in that era had a time concept spanning two to three hundred years. However, people today no longer have such a long-term vision.

I deeply understood this principle when I graduated from agricultural school and started farming. The crops I planted grew well, and the more time and effort I invested, the better they grew. Each stage had its own history. When dealing with nature, there are no shortcuts, and you cannot rush. The rice seeds sown in spring can only be harvested in autumn. No matter how much humans rush, nature will not respond because it follows its own process. No matter how much you rush, the rice cannot become full overnight, and trees cannot become robust instantly.

The Wisdom of Traditional Architectural Craftsmanship

I. "Build temples not by buying wood, but by buying the entire mountain."

The unique characteristics of trees, which can be thought of as their "heart," are influenced and determined by the specific environmental conditions of the mountain where they grow.

For example, a tree growing on a south-facing slope will have fewer and smaller branches on its north-facing side because it receives less sunlight. Conversely, the south-facing side will have many thick, strong branches. This type of terrain is constantly exposed to strong westerly winds, so the branches on the south side are bent eastward by the wind pressure. However, even though these branches are forced eastward by the wind, they still strive to return to their original position. All trees develop their own unique characteristics based on their growing environment.

The saying "don't buy wood, buy the whole mountain" means that you shouldn't buy trees that have already been turned into lumber, but instead go into the mountains to see the geology and the characteristics of the trees born from that environment.

Why is this important? Because you can't identify these characteristics after the trees have been processed into lumber.

Additionally, this saying also means that we should use trees from the same mountain to build a pagoda. If trees are pieced together from various mountains, their individual characteristics will be difficult to harmonize. That's why we need to go into the mountains to see the trees before buying them to build a pagoda.

Recently, going into the mountains to see the trees has become increasingly difficult. However, I went to the mountains of Taiwan for the construction of Yakushi-ji Temple and was deeply moved by the two-thousand-year-old cypress trees. I thought to myself, "It was worth coming to the mountains to see the trees." Because I went to the mountains and saw the trees, the constructed temple is without any regrets.

II. "The wooden structure of temples and pagodas should not be built according to measurements, but according to the tree's characteristics."

Trees growing to the east, west, south, and north should be used according to their orientation; trees growing on mountain ridges and slopes can be used for structural members; trees growing in valleys can be used for accessory materials.

This tells us how to use the lumber after buying trees from the entire mountain. Trees grown on the south side of the mountain should be used on the south side when building a pagoda. Similarly, those from the north should be used in the north, those from the west in the west, and those from the east in the east. They should be used according to their growing orientation.

Trees from the mountainside to the mountaintop should be used for structural components. This means that trees growing there receive ample sunlight, so they grow very strong. Especially the trees on the mountaintop, which not only receive ample sunlight but also grow with strong wood and characteristics due to wind, sun, rain, and snow. These trees with strong characteristics are most suitable for use in columns and beams that support the entire building. That's what this saying is telling us.

Trees growing in valleys have plenty of moisture and nutrients. In these places, sunlight and wind are insufficient, so the trees can grow smoothly, but conversely, these smoothly grown trees without personalities are not very strong. Therefore, they can only be used for decorative materials, such as decorating the ceiling or the railings of the roof.

Horyu-ji Temple is an Asuka period building, and Yakushi-ji Temple is a Hakuho period building. They were both built according to this saying, so the south side of the halls and pagodas use knotty wood. Conversely, there are none on the north side. If you look at the south side of the pillars of the east pagoda of Yakushi-ji Temple, it truly corresponds to the saying "six knots in one bay," meaning that there are six or seven knots in an area of about two square meters. The same is true for the middle gate of Horyu-ji Temple: there are many knots on the south side, and almost none on the north side.

Such wisdom has allowed ancient architectures to last for more than 1,300 years. I participated in the dismantling and major repairs of Horyu-ji Temple from 1934, and it lasted for nearly twenty years. This was the first dismantling and major repair since its construction.

III. Anti-Fragile Design Mechanisms.

In traditional architecture, each pillar has its own personality and strength. Therefore, they cannot be placed on the same stones. Because in an earthquake, all the pillars will shake together, but if they are fixed in the same direction, like soldiers marching, it will cause the building to not withstand the force and eventually collapse.

However, ancient carpenters would place pillars on natural stones, so the orientation of the pillar bottoms would be different, and even if an earthquake occurred, the pillars could adapt to the force of the earthquake according to their own characteristics. Because they are not fixed with rivets, the pillars can reset after shaking. This "floating" pillar method can effectively mitigate the impact of earthquakes.

IV. Counter-Intuitive Wood Selection.

Choosing the right wood is also very important. Some trees that look big and thick may actually have hollow trunks. Although these trees may appear young, they may actually be very old. Their branches absorb a lot of nutrients, making the trunk look tender and young.

Conversely, if a true old tree has concentrated nutrient absorption, the leaves may wither and turn yellow, but that does not mean that the tree itself is aging. Choosing this type of tree to build a house can give the building a unique style and quality.

V. Demonstration of Redundancy in Design.

When dealing with eaves and pagoda eaves, ancient craftsmen would extend the wood to the back so that if the front end was damaged, they could simply saw off the damaged part and pull the back part out to continue using it. This not only saved materials but also extended the life of the building. This method demonstrates how they cherished and used wood for a long time.

Due to length constraints, I will discuss How Traditional Architectural Craftsmanship is Passed Down in the second part.

As always, thanks for your reading and I hope you enjoy it.